The Destruction of Native American Religions

The Destruction of Native American Religions

The Destruction of Native American Religions

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states, inter alia, that the government “shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…”Sadly, while the application of the Amendment has been ongoing and effective where Judeo-Christian systems of belief are concerned, the application regarding Native American religions has been weak to the extent of being almost non-existent. An examination of the history of the denial of religious freedom to Native Americans reveals much.

The arrival of the Settlers

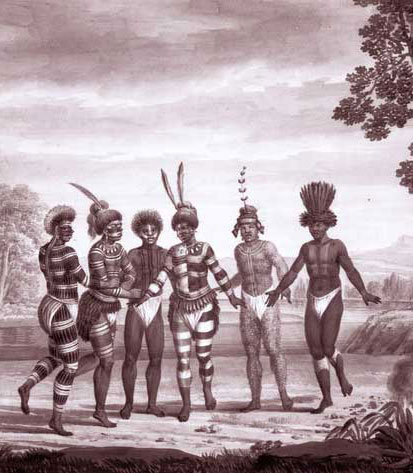

The Europeans who came to America did so in part, to escape religious persecution. Ironically, this search for freedom of beliefs turned, on arrival in the New World, into a defensive mindset that did not allow the acceptance of any other forms of belief. To be fair, one reason, although not a mitigating one, could be that the huge diversity of Native languages, cultures, and systems of belief made understanding strange faiths too much of an effort for people who were, in the early years, struggling to survive.

The War Policy and the Nez Perce Response to the 1863 Treaty, Schools and Churches (see Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee)

The inability to accept other religions was a major factor in the friction that developed between the settlers and the Natives. The results were violent conflict and the forced occupation of Native lands which in turn resulted in the creation of the reservations.

In 1863 a new treaty was presented to the Nez Percés. It took away the Wallowa Valley and three-fourths of the remainder of their land, leaving them only a small reservation in what is now Idaho. Chief Old Joseph refused to attend the treaty signing, but Lawyer and several other chiefs—none of whom had ever lived in the Valley of Winding Waters—signed away their people’s lands. The “thief treaty,” Old Joseph called it, and he was so offended that he tore up the Bible a white missionary had given him to convert him to Christianity. To let the white men know he still claimed the Wallowa Valley, he planted poles all around the boundaries of the land where his people lived.

Also Read: Native Americans and Their Role in Today’s Economy

Not long after that, Old Joseph died (1871), and the chieftainship of the band passed to his son, HeinmotTooyalaket (Young Joseph), who was then about thirty years old. When government officials came to order the Nez Percés to leave the Wallowa Valley and go to the Lapwai reservation, Chief Young Joseph refused to listen. “Neither Lawyer nor any other chief had the authority to sell this land,” he said. “It has always belonged to my people. It came unclouded to them from our fathers, and we will defend this land as long as a drop of Indian blood warms the hearts of our men.”He petitioned the Great Father, President Ulysses S. Grant, to let his people stay where they had always lived, and on June 16, 1873, the President issued an executive order withdrawing Wallowa Valley from settlement by white men.

In a short time, a group of commissioners arrived to begin the organization of a new Indian agency in the valley. One of them mentioned the advantages of schools for Chief Joseph’s people. Joseph replied that the Nez Percés did not want the white man’s schools.

“Why do you not want schools?” the commissioner asked.

“They will teach us to have churches,” Chief Joseph answered.

“Do you not want churches?”

“No, we do not want churches” Joseph responded.

“Why do you not want churches?”

“They will teach us to quarrel about God,” Joseph said. “We may quarrel with men sometimes about things on this earth, but we never quarrel about God. We do not want to learn that.”

It was only towards the end of the 19th century that the policy of subjugation of the Tribes through conflict was changed into one of forced assimilation. The “War Policy” thus became the “Peace Policy.” The new objective was to eliminate “Indianness” through a planned integration into the ideals, culture, and religion of the now dominant “White Men.” The now infamous boarding schools to which thousands of Native American children were forcibly sent to replace traditional beliefs with Eurocentric ones is a prime example of this policy. It was thought that instead of trying to eradicate traditional beliefs and faiths among adults, it would be easier to indoctrinate children with the new beliefs while they were deprived of parental guidance. Even though the schools were under the supervision of the federal government, the dictates of the First Amendment were openly ignored.

“Kill the Indian, and Save the Man”: Capt. Richard H. Pratt on the Education of Native Americans

Beginning in 1887, the federal government attempted to “Americanize” Native Americans, largely through the education of Native youth. By 1900 thousands of Native Americans were studying at almost 150 boarding schools around the United States. The U.S. Training and Industrial School founded in 1879 at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, was the model for most of these schools. Boarding schools like Carlisle provided vocational and manual training and sought to systematically strip away tribal culture. They insisted that students drop their Indian names, forbade the speaking of native languages, and cut off their long hair. Not surprisingly, such schools often met fierce resistance from Native American parents and youth. Carlisle founder Capt. Richard H. Pratt at an 1892 convention argued his perspective that highlighted his pragmatic and frequently brutal methods for “civilizing” the “savages,” including his analogies to the education and “civilizing” of African Americans.

The Next Step

Despite all the efforts, it was not possible to eradicate “Indianness”. In 1883, the Secretary of the Interior told the Commissioner of Indian Affairs that traditional Native American dances were heathen and that traditional medicine men were exerting undue influence over the Native population and so should be stopped. In response to these and other absurd allegations, the “Code of Indian Offences” was promulgated that outlawed many of the traditional religious beliefs and cultural practices of the Tribes.

A Change and the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act

In 1934, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs issued a circular that stated “No interference with Indian religious life or ceremonial expression will hereafter be tolerated. The cultural liberty of Indians is in all respects to be considered equal to that of any non-Indian group.” In 1978, President Carter signed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) which accepted that government policy had prevented Native Americans from practicing their religions.

But the changes came very late. Much of the religions and way of life of the Tribes had already been lost Still, efforts are now being made to create an awareness of the values and importance of Native American religions and how they can contribute to the growth of the homeland of the Tribe, the United States of America. The efforts of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of California are an example of what is being done to restore Native American religions.

In essence, the Code of Indian Offenses did not allow Native Americans to freely practice their traditional religions. Such discrimination would be considered unconstitutional under the First Amendment if Native Americans were considered United States citizens, however, the rights and privileges held by citizens of the United States were not granted to Native Americans until 1924. In addition to this, the vast majority of white Americans considered the First Amendment to apply only to Christianity, which is why the little protest was raised in response to the unconstitutional legislation; to them, “religious freedom” simply meant that Native American tribes were free to join whichever Christian sect they deemed best.

Also Read: The Politics of Erasure and the Missing Tribal Name in Bay Area History

In 1978, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) was enacted to return basic civil liberties to Federally Recognized Native Americans, Inuit, Aleuts, and Native Hawaiians, and to allow them to practice, protect, and preserve their inherent right of freedom to believe, express, and exercise their traditional religious rites, spiritual and cultural practices. These rights include but are not limited to, access to sacred sites, freedom to worship through traditional ceremonial rites, and the possession and use of objects traditionally considered sacred by their respective cultures. However, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act does not apply to previously federally recognized tribes such as the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe or historically unrecognized tribes.

Even under the act, however, tribes did not have the First Amendment rights for certain religious practices, notably, the sacramental use of peyote. This was upheld in the 1990 case Employment Division v. Smith which held that the First Amendment does not protect the sacramental ingestion of peyote in Native American religious ceremonies from criminal sanctions.

- May 05, 2023